“Write a letter in the voice of your childhood self,” the writing prompt read, staring at me from the page. I held my pen over it, urging my inner child to peek out of her shell, but she didn’t budge from wherever she was lodged inside me (somewhere in my chest, I think, just below its cavity). I tried as hard as I could to think back to my childhood days, to connect with whatever my little girl voice may have sounded like. I couldn’t get my internal monologue to sound like her, no matter how much I looked into the past. I started writing anyway, hoping that I’d find her along the way, but I spewed out nonsense that sounded nothing like me, utterly disconnected.

I remember writing my first song when I was seven years old, hearing that songwriters made more money than singers, and immediately deciding to make that my career. It was fun and, supposedly, I could make a living out of it; how could it get better than that? But my love for writing quickly snowballed into something greater than the prospect of riches—I wrote a full-length fantasy trilogy when I was eight. I hand-wrote a novel in a small notebook and passed it around to my classmates for them to read, filled with pride when an especially sad scene made them cry. Some short years later, at around ten years old, I’d figured out that writers didn’t make as much as I’d hoped. At this young age, I started thinking of how I could make a profitable career out of this, hyperaware that a life as a writer depended on getting eyes on my work. So, I pushed myself to write better, imitating the adult authors I hid under my pillow.

“I don’t remember how to write as a child,” I confessed to the journal prompt. “I don’t know if I ever did, besides the first song I ever wrote. I think my words grew up before I did. When was the last time I created just to create?

“I’ve always had a desire to be consumed.”

“I’m gonna live there one day,” I said to my childhood best friend on my fifteenth birthday as we looked out the window of the Museum of Modern Art. Next to the sculpture garden was an apartment building that I fantasized about living in. It was my first time ever at the MoMa, and it would soon become tradition to visit on my birthday. I was obsessed with Van Gogh at the time and wore a blue and yellow outfit to match The Starry Night. My cousin told me I looked like a minion, but that wouldn’t curb my enthusiasm.

“I’ll live in that one,” my friend said, pointing to the building next to mine. “And I’ll work in the nearest hospital. You can babysit my kids while you write all day.”

My dreams of being a writer were always well-known, and so was my love of New York. The closest I’ve ever had to a hometown was Newark, a short train ride away from the city. I grew up taking the train to 33rd Street and falling in love with the hustle and bustle of it all. I’d fantasize about being an adult, walking the streets on my way to work as a writer for some magazine, à la 13 Going On 30 and Devil Wears Prada.

I’ve always been a big dreamer, and maybe that’s because I’ve always been a creative. Not once in my life did I ever think that I would settle in a “real job”, whatever that means in today’s gig economy. The thought of it never even crossed my mind until recently, curiosity scratching at my brain, asking if this is all there is. I’ve worked my whole life towards having a creative career, and the older I grow, the more I have to think about how to accomplish it realistically. But what’s “realistic” for, frankly, one of the most unrealistic fields?

My career (to put very graciously) as a writer thus far has mostly, almost entirely, consisted of myself simply being vulnerable on the internet. Because this is the easiest way to gain trust with an audience: oversharing (you know my thoughts on this if you read my personal essay on the topic). For those of us who aren’t tapped into the industry—which is unfortunately one of the driving points of creative success, as I’m sure you know from the nepo-baby discourse going around—being online is the career of most creatives today.

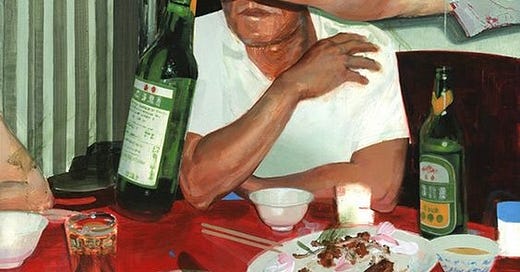

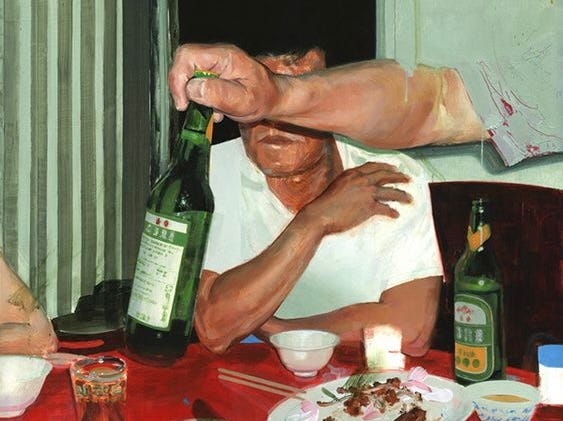

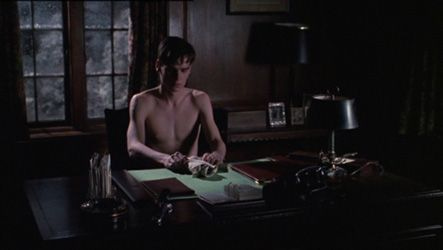

We sell our vulnerability to the claws of consumerism, and maybe, just maybe, if we’re lucky enough to become immensely successful, we can afford a modicum of privacy. For big celebrities in the industry—specifically actors and singers—it’s unfortunately normal, and often encouraged, to be stripped of even a semblance of personal life, and it’s been this way for decades. However, the act of doing this to “smaller” or upcoming artists is still fairly new.

In Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney, one of the main characters, Alice, is a famous novelist who got a book deal and skyrocketed into fame. She expresses how this was once all she ever wanted, but now she can’t understand why people would want to know about the author behind a fictionalized novel. Near the end of the book, Alice does an interview where she says that her partner hasn’t read her books, which garners a lot of internet hate from supposed fans who argue that she should be with someone who appreciates her work. She expresses her confusion on this to her partner. Why would these people ever think that they know what’s best for her? They’ve only read her books; they have no idea who she is. And yet, they feel entitled to not only her work, but her, as a person.

Through talking about mutual frustrations with my creative friends who make their living online, we often come to the same conclusion: whenever we want to boost engagement on our feeds, we have to post a tragedy. A trauma. An intimate moment, thus ruining it from being exactly that. And then, if we’re lucky, we might be able to show our art somewhere in there. The internet doesn’t want to just hear about our crucifixion; they want to witness it.

You might know all of this already. It might be why you’re reading this. You want the viral recipe, the perfect story, the moment it all comes together. In a video I posted recently where I talk about all this, I mention how the algorithm leaves little to no room for creativity. You won’t get eyes on your work unless it’s a trend or a four-second reel or a crying video, but I do not want to—I cannot—live in a world of four-second reels. But will I contribute if it means my work is seen? If it means that people will read what I write? If I can harbor connections this way? If I can pay my bills by doing what I love, even if I have to do a little bit of what I hate sometimes? Yes. Always.

I never thought I’d say this, but Trisha Paytas offered the best semi-solution to these creative struggles: support artists directly, in any way you can. Instead of using streaming platforms that pay artists not even a single cent per stream, she purchases directly from iTunes in an effort to support their work. Although she’s a millionaire, you don’t have to be one to do the same. iTunes charges $1.29 per song, and nearly half of that goes directly towards artists. No, you don’t have to cancel your Spotify, but you can apply the same idea to support creatives in different ways.

Look, fine, I’ll give you the looping reels. I’ll give you the clips that tell you nothing and everything about me. I’ll give you not just the art that stemmed from the trauma, but the trauma itself. The crying videos, the transformation sequence, the redemption arc. Just tell me, in return, that you’ll read. Tell me you’ll buy the art, the merch, the self-published book. Tell me it has a place on your wall, in your journal, your bookshelf, that you sent it to your mom and she thought it was weird and tell me that you didn’t care because, actually, you cared a lot. Tell me you’ll buy the physical copy and you won’t return it. Tell me you’ll comment and share when a creator you enjoy decides to experiment with their content. I’ll give you the worst of me in exchange for the best of you. I’ll give you more to consume as long as you promise you’ll always be hungry. Is it a fair trade? Do we have a deal?

If you follow me on my social media, you know this is a topic that’s been on my mind a lot lately as I struggle to figure out what direction to take my content. But my writing is always here, and always for you.

My last personal essay was on a similar topic, but I wanted to make this one more directed towards creatives. If you only take away one thing from this essay, I hope it’s this: support your artists, Trisha-Paytas-style. Whether you’re a consumer or an artist yourself, there is always so much to share and support. Creativity makes the world go round, and we have to do our part to keep it that way.

Some housekeeping, per usual: If you’re looking for Valentine’s gift for your bookish lovers or friends, or just want to buy some new books, I now have a storefront with Bookshop.org. Click here to see a list of some of my favorite books, and 10% of your purchase is donated to local bookstores.

If you enjoy my work, I hope you’ll consider sharing or commenting on this post, tipping through this link, buying my book, subscribing, or updating to a paid subscription for just $2.50 a month where you’ll get full access to all my previous paid essays + extra writings every month, which you can do with the button below.

Thank you for being here. Love you always.

Yours forever,

✮ Paula ✮

Your work is so fulfilling 💖. And I envy you for knowing your passion so young. Cause I feel it's harder to live in this "real" world being lost.