Legend says that there’s a room that knows everything, but I don’t know what to ask it. Things have a way of making sense eventually, and interrupting this process feels bold, in an almost illicit way, like a villain disrupting the natural order of things. I don’t think I’m the bad guy of whatever story I’m writing; but if I were, I don’t think I’d want to stop it either. If walls could talk, I think I’d request they take a vow of silence until I’m gone.

In late May, soon after my college graduation, I received a check for my first ever official freelance writing gig—$500 deposited into my bank account, for a full month of work, which couldn’t even cover my California rent. I knew that my previous Doordashing and dog walking jobs paid me more, but that $500 was the first time I’d gotten paid for a job that was completely dependent on my ability as a creative writer. It was my first semblance of financial stability in a career as a writer, and it was all mine.

Later that same day, at a doctor’s appointment, the nurse asked me what I do for work, as a way to distract me from having my blood drawn. I said that I was a writer, and I surprised myself with the truth of those words. I am a writer, for real now, in a more realistic than fantastical sense, for the first time in my life. I do write for a living; it’s how I make my income. And I almost wanted to laugh. Wasn’t this everything I’ve always wanted? And now it was here suddenly, almost without warning. I was holding it with both of my hands, and it wasn’t running away from me this time. Writing felt at home with me, and I with it.

But now, in late December, I call my friend and talk about leaving the country, again, because this time I think I’m ready (but I wasn’t before, and I’m probably not now). I don’t have time for my personal writing anymore, I have a novel draft that sits untouched, but maybe European air will change that (it won’t). We both talk about needing new friends, and environments we can grow in, and how majorly lost we both feel.

She says something like, “I’m miserable and confused, but I also feel like I know myself a lot better.” I say something like, “I can relate to being miserable and confused, but I feel like I might know myself less.” And she laughs, and I laugh, and I don’t say that I’m jealous of her newfound self-knowledge, although I am, and instead say a different truth: “I’m not the worst. But I’m also not, like, fabulous.”

And she cackles, and I mean, truly a cackle, because for some reason using the word fabulous in this context is the funniest thing ever to us. She says that should be the title of my next essay, and it’s not, but I hope she’ll settle for a subtitle.

That sentence somehow felt like the perfect encapsulation of what we’d both been going through since graduating college, what we’d been building up to ever since the clock struck midnight on our 20th birthdays. In a less fab way of saying it, the teenage identity I’ve meticulously built since I was thirteen has been stripped of any familiarity. I feel like I’m waiting for the bus and don’t have any change in my pocket, let alone a map to tell me where to go in the first place, and I’m at the complete mercy of strangers around me.

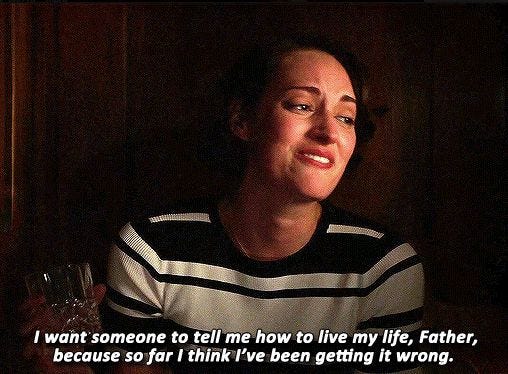

When I first watched the show Fleabag, I didn’t understand her monologue to the Priest in the confessional. “I want someone to tell me what to wear every morning,” she began. “I want someone to tell me what to eat. What to like. What to hate. What to rage about. What to listen to. What band to like. What to buy tickets for. What to joke about. What not to joke about. I want someone to tell me what to believe in. Who to vote for and who to love and how to...tell them. I just think I want someone to tell me how to live my life, Father, because so far, I think I’ve been getting it wrong.”

This seemed miserable to me at the time. Why would I ever want someone to control my life? My every waking moment? It didn’t seem like a life at all, and it still doesn’t. But I could see the temptation in it recently, as I looked in the mirror doing my 5-step skincare routine before going to bed, trying to heal acne scars that wouldn’t seem to go away, and I wished that someone could analyze me—all of me—like some dystopian and even scarier version of the current AI technology we hold, and tell me exactly what I needed to do to live a perfect life. A life with stability, where all of my current needs and maybe even a couple of wants are met. Give me a foolproof plan that will work. I’m sick of my attempts. I’m sick of getting it wrong. Put me on the right path, the right bus with change to spare, and I promise I’ll stay there this time.

In 2023, I’ve moved about eight times. Eight times, I had to pack up my belongings as much as I could, and go in search of a new house that I prayed would be a little less temporary. Six of these times were between June to October alone. I stopped hanging up the wall art I’d collected and instead tossed them onto whatever desk the room had come with. I was so tired of having these stupid pictures sitting on furniture that wasn’t mine, and leaving behind parts of myself in every room I’d barely lived in. I wanted somewhere I could die in, and it’d take them months to find the body. I wanted my body to grow roots into the floorboards. I craved stillness, in a way that I’d never craved before. Everything was always go, go, go. Whenever I got somewhere, I started thinking about the next thing immediately. I didn’t know how to breathe without thinking of the future. I think I still don’t, but I’m starting to learn.

The last time I was carefree, I was eighteen and wanted everything. I write about her a lot, so you might be sick of hearing about it, but it’s difficult for a writer to stop writing about something they both love and miss. And I miss that version of myself often. I’ve decided to let her go, whether for better or worse, but I keep her alive in me as much as I can. I bought a new crystal recently and thought of her. I saw someone wearing a shirt they clearly cropped by hand, and thought of her again. I recently thought of buying a mini photo printer for myself and remembered the various shrines that adorned her old dorm room. I live alone now, and I try to channel her whenever I go out alone. She went everywhere alone, unafraid, talked to strangers shamelessly, and she did it so well. She was, in the simplest of terms, fabulous.

Fleabag, you weren’t getting it wrong. I’m not either. We’re just doing our best, and sometimes the best we can do is pull from our pasts, the lives we’ve already lived, and the lives we want to live that we have yet to see. Maybe we had the right idea, of the whole life control thing, but we were asking the wrong people. Why are you asking the priest? Why am I asking my current self, who’s lost and clueless and far from fabulous?

When I was in my early teens, I discovered most of my music on my own, usually through lots of scrolling on YouTube. I found a song with the artist’s voice as the intro, saying, “Hi, my name is Mitch Welling. I’m nineteen years old. Would you like to hear a song?” I remember listening to Mitch Welling at 14, thinking that the 19 he spoke of was so far and beyond my imagination. I return to him when I’m 21, and my hands are still the same. They’re always the same.

With these too-familiar hands, I reach now to the future. I try to see myself when I’m 33 or 67 years old, the same way fourteen-year-old me tried to see five years into her life. I ask her how she’s doing, how she remembers the time I’m in now. My future self writes about me the way I write about my eighteen-year-old self.

The room that knew everything knew too much, felt too cold, too wise; but she knows me, and is just wise enough to tell me how to get through this. How she got through it before. She excuses pleasantries—we’ve been through this before—and I ask her what to do. What to wear. What to eat. What to like. What to hate. She tells me it’s happened before, and I know that. And we know: it’ll happen again.

“I know that scientifically nothing that I do makes any difference in the end, anyway, I’m still scared,” Fleabag said to the priest, and I say to my future self, who’s not 21 anymore and doesn’t remember the conversation I had with my friend about not being fabulous. She doesn’t remember the bus or the lack of change. The future is so big, and these moments I’m in now are so small.

Fleabag asked the priest desperately, but I ask my future self softly, holding hands that I’d recognize on anyone, anywhere: “Why am I still scared? So just tell me what to do. Just tell me what to do.”

She smiles at me and doesn’t say a word. It’s all the confirmation I need.

I am full of feelings and not a lot of thoughts! So I hope this makes sense!

Happy almost New Year, or Happy New Year, depending on when you’re reading this. I hope we all connect to our older selves this year and look to the future, but not too much. The key is balance! Figuring that out now!

BTW, if you’re looking for a belated Christmas gift or early Valentine’s gift, or just want to buy some new books, I now have a storefront with Bookshop.org. Click here to see a list of some of my favorite books, and 10% of your purchase is donated to local bookstores!

If you enjoy my work, I hope you’ll consider sharing or commenting on this post, buying me a coffee, subscribing, or updating to a paid subscription for just $2.50 a month, which you can do with the button below. Paid subscriptions have been paused for the past month or two, but it’s getting a full revamp starting in January, and I hope you’ll be a part of it.

The next post of Under the Bed will be out this Sunday to kick off 2024 with my personal fashion philosophy and how to develop your own. Hope you’ll tune in. Hope you’ll follow along. Hope you’ll still be here in the New Year, and for a while to come.

✮ Paula ✮